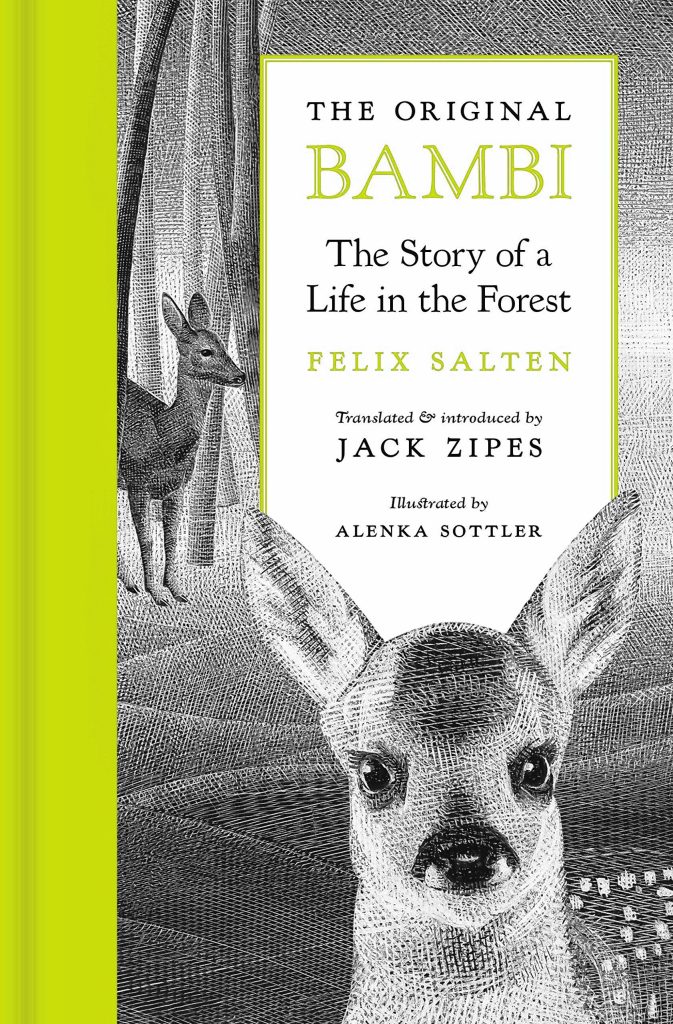

The Original Bambi: The Story of a Life in the Forest

By Felix Salten

(161 pages, fiction, 2022)

I know what you’re thinking: “Bambi, seriously?” Stop right there! This new release from Princeton University Press is, to put a new spin on an old cliché, not your grandparents’ Bambi. In this version, translator Jack Zipes aims to improve on the original 1928 English translation, capturing the intent behind Felix Salten’s 1923 German-language novel. Alenka Sottler’s gorgeous black-and-white illustrations veer more toward naturalism than the cutesy anthropomorphic fawn and friends from Walt Disney’s 1942 animated film adaptation. In fact, if your idea of Bambi comes from the Disney film, you will likely be surprised by the darkness of the original story.

You’re probably familiar with the broad strokes of the plot: a deer named Bambi is born in the forest, is orphaned, and comes of age. This novel, like the animated film, is told from the forest creatures’ perspective. Salten, an avid hunter and outdoorsman, excels in his lush descriptions of the natural world and the many forms of life that, together, create a forest ecosystem. The story includes death and violence (plenty of each), but most animals kill one another out of midwinter desperation, rather than malice. The true antagonist in this story is Him — always capitalized, the punctuation implying omnipotence — mankind, which disturbs the peace of the forest and butchers animals for sport. Man’s sin is all the greater, according to Salten, because it’s based in unfair power dynamics. It’s not that killing is unnatural (Salten makes it clear that death is a part of life, in the wild), but that man wields his power over animals to damage and destroy. The animals bond in their common enmity of, and victimization by, humans.

The real-life historical context in which Bambi came to life was anything but an idyllic forested wonderland. Salten was an Austro-Hungarian Jew, writing this story from Vienna just a decade after the “Great War” ravaged Europe. There are many interpretations of Salten’s intent in this work — but for me, it was almost impossible not read it as an allegory for 20th century European anti-Semitism. Certain scenes and characters represent themes of assimilation, isolationism, self-determination, and Zionism that would have especially registered with Jewish readers in the 1920s, ‘30s, and ‘40s. (Evidently, the Nazis also saw these parallels, as Bambi was banned by the Third Reich.) Power dynamics are key, the “bad guys” are larger-than-life, and everyone must fend for him – or herself to ensure survival for another season. Unsurprisingly, the melancholy fate of our friend on the page is not nearly as rosy as the happily-ever-after of Disney’s Bambi. The conclusion can be read as cynical — but would such pessimism not be understandable, even sensible, being written from (and to) post-World War I Europe?

All things considered, I found this book to be worth stretching outside my comfort zone. This novel re-introduced me to a story with more depth than I’d expected, and I was able to enjoy Bambi’s tale with fresh eyes. As a bonus, this title fulfills several categories in the Concord Public Library’s Ultimate Book Nerd reading challenge, including: published in 2022 (the new translation); told from an animal’s perspective; published before 1950 (the original text); written in third person; turned into a TV show or movie; translated; banned or challenged (in Germany); and recommended by library staff.

Visit Concord Public Library online at concordpubliclibrary.net.

Faithe Miller Lakowicz