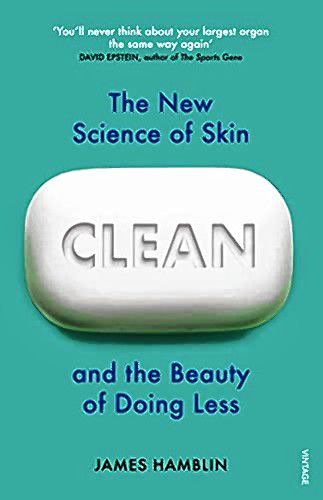

Clean: The New Science of Skin

By James Hamblin

(280 pages, nonfiction, 2020)

I often enjoy nonfiction titles that promise to share “the new science” behind a quotidian topic —and in that vein, Clean: The New Science of Skin does not disappoint! In this work, Dr. James Hamblin — a physician specializing in preventive medicine and public health, staff writer for The Atlantic, and lecturer in health policy at Yale University — encourages readers to use fresh eyes to view skin and its role in the human body. “Skin is no less vital than our heart or spine or brain,” he says. “Without it, the fluids that compose us evaporate, and the outside world pours into us and infects us and we quickly die.” That’s a pretty compelling point.

In very broad terms, the thesis behind this book is that mainstream practices in cosmetics and dermatology assail our skin — the body’s largest organ, our interface with the outside world — with unnecessary interventions, and that human skin actually requires very little to maintain baseline health and hygiene. In fact, Hamblin himself hasn’t showered, in a traditional sense, for a number of years. This is not to say that he doesn’t practice good toilet hygiene, wash his hands when necessary, or partake in personal grooming. Rather, Hamblin has shifted away from submersing himself in water daily and applying bar or gel cleansers to his hair, face, and body; instead, he utilizes water when and where it’s necessary, styles sans chemical products, and leaves the soap for his hands. (This book was published just before the COVID-19 outbreak, which Hamblin addresses in his introduction. This does not, in my opinion, detract from his overall idea, which is that we do far more to our skin than we usually need to.)

Hamblin explores the less-is-more skincare philosophy through a number of avenues, from medical history to interviews with scientists conducting cutting-edge research. He argues that the current skincare landscape is largely dominated by advertisers (whose job, of course, is to convince us to buy products, whether or not we need them and regardless of how well they actually work). One major area of focus is the skin microbiome: the system of tiny mites, bacteria, fungi, and other miniscule organisms that live on our bodies and are, perhaps, essential for our overall health. Much in the way that over-prescribed antibiotics can lead to drug-resistant germs, Hamblin believes that over-cleansing with alkaline soaps actually does more harm than good, because it destroys or disrupts our delicately balanced microbiomes.

This is a quick, lighthearted, and informative read that will appeal to lovers of popular science. I hope it also challenges you to interrogate some of your own ingrained preconceptions about what it means to be “clean,” and how you might make small changes to your daily routine to push back against the status quo. I found it particularly fascinating to learn about the (lack of) regulations in the U.S. cosmetics industry and to think about the ways that skincare sits at the intersection of health and aesthetics. What is your favorite chapter? Make sure to stop by the desk at CPL and let me know!

Visit Concord Public Library online at concordpubliclibrary.net

Faithe Miller Lakowicz