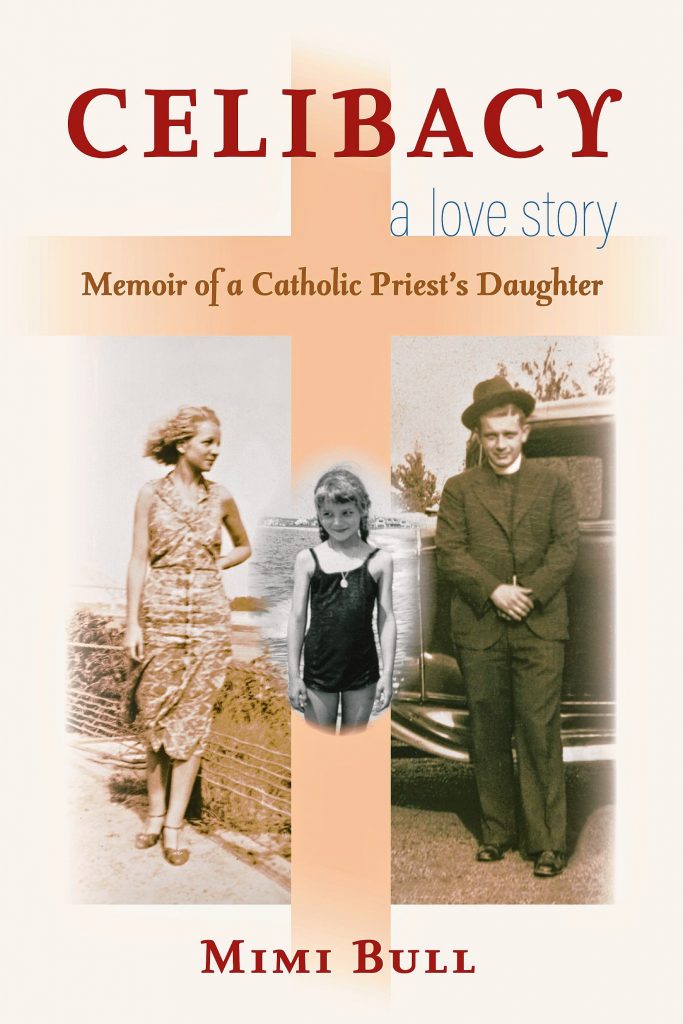

‘Celibacy – A Love Story: Memoir of a Catholic Priest’s Daughter,” by Peterborough author Mimi Bull, is out now via Bauhan Publishing and is available at Gibson’s Bookstore.

Born in the 1930s, a time when unmarried pregnant women were whisked off in secrecy and their babies given away, Mimi Bull grew up believing she’d been adopted by two women, a mother and daughter. Not until she was a mother herself did she learn that those adoptive parents were her blood relatives – her grandmother and her mother.

It would be another dozen-plus years before she discovered the identity of her father: the Catholic priest she’d known as a close family friend. The stories she’d been told in childhood had been concocted to hide her father’s broken vow of celibacy and shield her mother from the disgrace of unwed pregnancy.

In this memoir, Bull writes lovingly of her parents and of their extraordinary efforts to forge a life as a family while keeping these enormous secrets. Yet she also reveals the toll that secrecy took on her – evidenced in large part by her lifelong struggle with depression and a yearning to understand who she was and where she belonged.

Even after learning the truth of her parentage, and living a full life with her own family and the adventures of living in interesting places – her husband was a headmaster and the family was posted at schools in places ranging from Istanbul to San Antonio – Bull spent years trying to reconstruct her story. When she turned 80, she finally spoke to someone with a similar life story: an Irishman who learned as an adult that his godfather, a local priest, was really his biological father. It was the first time she had ever talked with another priest’s child.

Making that connection was momentous. Bull ends her memoir with a candid letter to Pope Francis, stating, “Just as the secrecy deprived me of feeling a part of either my mother or father’s family … so the secrecy and shame has kept priests’ children from the comfort and support of knowing one another. .. The Church .. swept us all under the rug to save its reputation. It never considered the human fallout from its failure to acknowledge us, the blameless children, much less offer compassion for our plight.”

Though her parents’ secrecy provided the backdrop to her early life, she is insistent that she doesn’t see herself as a victim, since her parents did the best they could, given their circumstances.

The following is an excerpt from the book.

Part One

Even though, growing up, I didn’t spend a lot of time thinking about my status as an adoptee, it was the back story to my childhood. I’d been told that I was adopted early on, and more information filtered down as I grew into adulthood: Alice Foyette adopted me in July of 1937 in Philadelphia when I was eight-and-a-half months old and brought me back to Norwood, Massachusetts, to live with her and her grown daughter, Florence. . . . Adoption set me apart. I was the only adopted child I was aware of. If others were adopted, one didn’t know because such things weren’t discussed. In my case, however, as the child in a family of two women, my adopted status was necessarily known. It simply “was what it was” in my mind and that was that. . .

My first inkling that I wasn’t who I thought I was came years later, when I was thirty-four. Florence, whom I’d considered my adoptive mother since Alice’s death in 1943, had come down to Princeton, New Jersey, where I had recently moved with my husband, Neil, and our three children. Since my childhood, I had been accustomed to having serious talks with my mother in the car while driving somewhere, anywhere. A few days into her visit, she asked if we might go off together for the afternoon. . . . We were driving through the farmland that surrounded Princeton in those days when she turned to me and said, “Mimi, I want you to know that I am your real mother.”

It blinded me as one is blinded by light after a blindfold is removed. At that moment of confusion, I could only grasp my supreme sense of happiness in knowing that this woman whom I so loved was indeed my real mother and not my adoptive sister/second adoptive mother, as I had been raised to believe. Out of blurred recollections of childhood, I remembered the day when I was six, shortly after Alice died, when Florence had suggested to me that now I should call her “Mummy.” That had been as easy for me as putting on a new blouse. She had been my sister, always there and as dear to me as her mother, Alice, had been. Hearing me call her “Mummy” for the first time must have been for her a deeply charged experience. . . .

My mother had made her difficult disclosure and that was the end of the truth-telling. For when I posed the inevitable follow-up question, “What about my father?” she answered casually:

“Oh, he never knew about you. It was a brief encounter, I was innocent about sex, and I never saw him again.”

“Who was he?”

“A business executive from Pennsylvania. I’ve forgotten the details.”

Part Two

Air travel was still in its glamorous stage in 1960. One dressed well, and for my departure, a group of family and friends gathered with champagne and gifts and encouragement. It was a sendoff similar to what one might have expected in those early days sailing the Atlantic on a Cunard liner.

Not yet twenty-four, I was making this long trip alone with two young children, one of whose health was compromised, on the old Pan American Flight 1, which circled the globe in a westward direction. By now, the two-and-a-half-month separation from Neil had overtaxed my patience and I could think of little else but arriving in my new home and settling in with my family to start a new life. The people gathered at the airport in New York shared my mother’s misgivings and concerns at my setting off into an unknown world. In those days, little was known of Turkey and the most recent news was of a coup d’etat, when the army took over the government of Adnan Menderes. Martial law prevailed, and had my mother known that there were heads hanging from the Galata Bridge when Neil arrived, she would have staged her own rebellion. I was oblivious to all of their concerns, aware only that I would soon be with Neil again and would be introducing him to his second son, Sam. . .

I was an eyewitness to an event that has entered Robert College lore. One morning, as I walked up the path from our house to the campus, I found a large dump truck parked in the lot above our garden. A strong odor came at me as I realized the mammoth gray mound on the truck was the carcass of an elephant, its inert trunk dangling over the side. My husband arrived to tell me that Lee Gardner, the biology teacher, had heard the elephant had died in the Istanbul Zoo and had immediately hatched a lesson plan for his unsuspecting students. They would dissect the elephant and then assemble the bones as an exhibit for the college’s small natural history museum. Maggots were needed to clean the dissected bones and had to be ordered from the States, post haste. . .

The same Lee Gardner called me one day and asked if I would take in three orphaned brown bears. Their mother had been shot in the Ataturk Forest and he, of course, immediately planned a zoo for his students. I couldn’t resist and that afternoon, a sturdy, waist-high cardboard packing box was delivered to my kitchen. Inside were the bear triplets with their eyes still closed, a delectable sight. Lee provided a small, nippled bottle and some vague clues as to their feeding, and left me to get on with it. I worked out a system of feeding them individually. Before they woke, I took one cub, fed it, and placed it elsewhere to enjoy its sleepy fullness. I then fed the other two in turn so that as they grew more lively I wouldn’t have to deal with their insistent squalling. At the end of the process, I would take the three in my lap and give them each a finger to suck on. Soon I’d have a lapful of purring cubs, roaring their content. If my doorbell rang often before, it rarely stopped now as news of the cubs spread. To manage this disturbance, I made a batch of vodka and mixed up several large apothecary jars of Bloody Marys and invited the community for an afternoon reception to meet my bears. They were a great hit and some semblance of peace was restored to my house.

Part Three

In the days following the funeral, I worked on the poignant job of disposing my mother’s books and personal items. . . .

At the very back of her closet, I found a green metal strong box roughly the size of the banana and lemon breads my mother loved to bake and serve to friends. It was locked. I felt conflicted about what to do. Clearly the box was something she had hidden, yet I wanted to be open with Jack as I cleared and sorted his wife’s belongings. Florence had left me her jewelry, but in going through it with her, we came across several valuable diamond rings left to her by Jack’s sister; I returned them to Jack for his daughters. With that in mind, I showed him the green box, which he did not recognize. I asked him if there were a cache of orphan keys kept for such a situation. He helped me look, without success, and then suggested I take it to a local locksmith. Unable to open the box while I waited, the locksmith told me to leave it with him and that he would drill it open. Several days later, I went alone to reclaim the box. I paid him and carried it back to the car to discover what it held. It was a sunny New England October afternoon as I sat there in the warm car with the box in my lap, wondering what I might find inside.

Many of us have a secret repository for the relics and the reminders of our life’s hot spots, a container to open in private and to touch, to reread, to savor again the tangible souvenirs of significant connections in our life. . . .

The first thing I realized as I began taking out the items inside was that this was not my mother’s secret repository. It was my father’s. In this box, which had probably been locked since his death in 1955, were the few intimate mementos of his secret family.

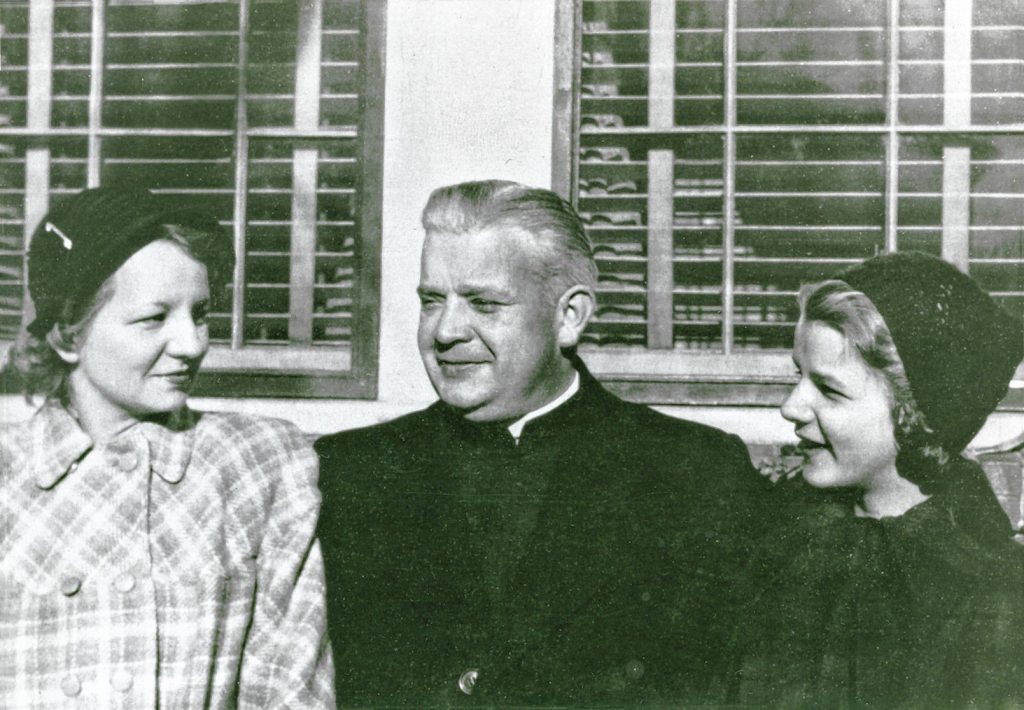

The first item in the box was a small, tan pigskin folder holding two professionally taken photographs: one of my young mother seated with her arms around a five- or six-year-old me, the other a portrait of me from the same session, outfitted in a finely smocked polka-dotted dress with a small white linen collar, my hair curled for the occasion. The small folder was from London Harness, the Boston shop for fine leather goods. It was clear my mother had had these pictures taken as a special gift for him.

Tucked behind the pictures were three small snapshots of her that must have been favorites of his. With these pictures was a shot of him as I had never seen him, slim, standing with friends against a black car, vintage mid-1930s. He wears a clerical collar and a hat pushed back at a cavalier angle. It must have been taken when he returned from the seminary and met my mother. On a scrap of white paper, I found his pencil sketch of her in profile and several drawings of me with pigtails.

Among the few papers, I discovered one that affirmed my status: an official document from the state of Massachusetts granting him legal guardianship of me. It was dated within months of my grandmother Alice’s death in 1942. He and Florence must have realized that should anything happen to her, this legal guardianship would give him legitimate claim to my welfare and well-being. Here was proof of the validity of my calling him my guardian, as I always had, without realizing that he was indeed my legal guardian, not to mention my father. With the discovery of this box, almost all the pieces of my story had finally fallen into place.

Mimi Bull, a native New Englander, raised her three children while a headmaster’s wife at schools in Istanbul; Vienna; Sedona, Arizona; and San Antonio, Texas. In her 50s she received a master’s degree in counseling, with a concentration in geriatrics. In 1987 she and her husband, Neil, bought a house on Old Jaffrey Road in Peterborough, where she has lived full time since 2004. Bull will visit Gibson’s Bookstore on Jan. 23 at 6 p.m.