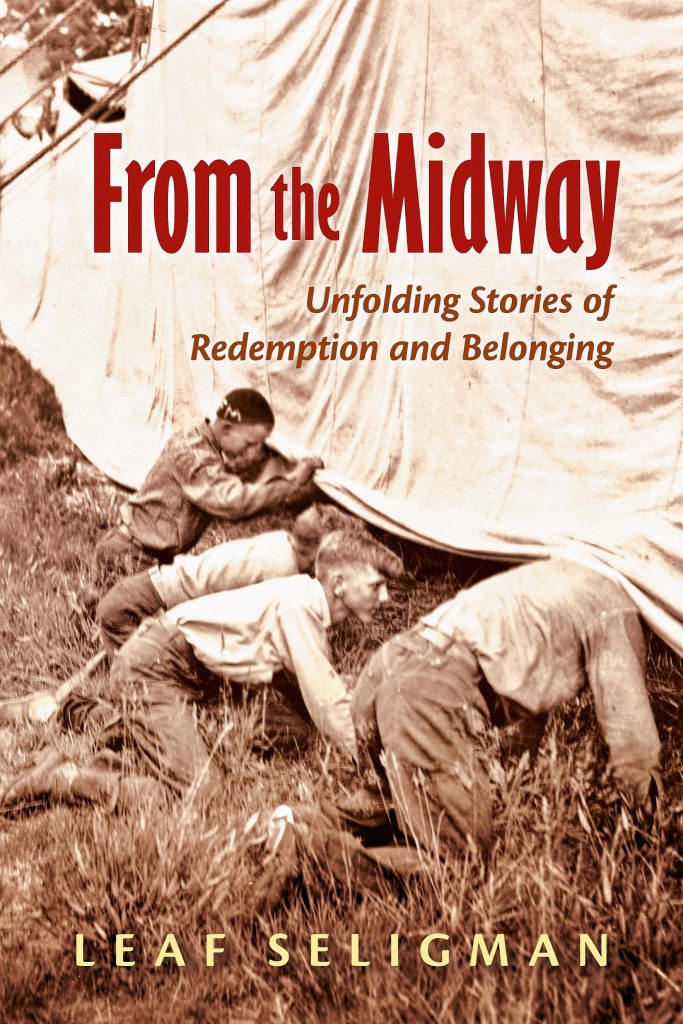

‘From the Midway: Unfolding Stories of Redemption and Belonging is out now and available at Gibson’s Bookstore or through Bauhan Publishing in Peterborough.

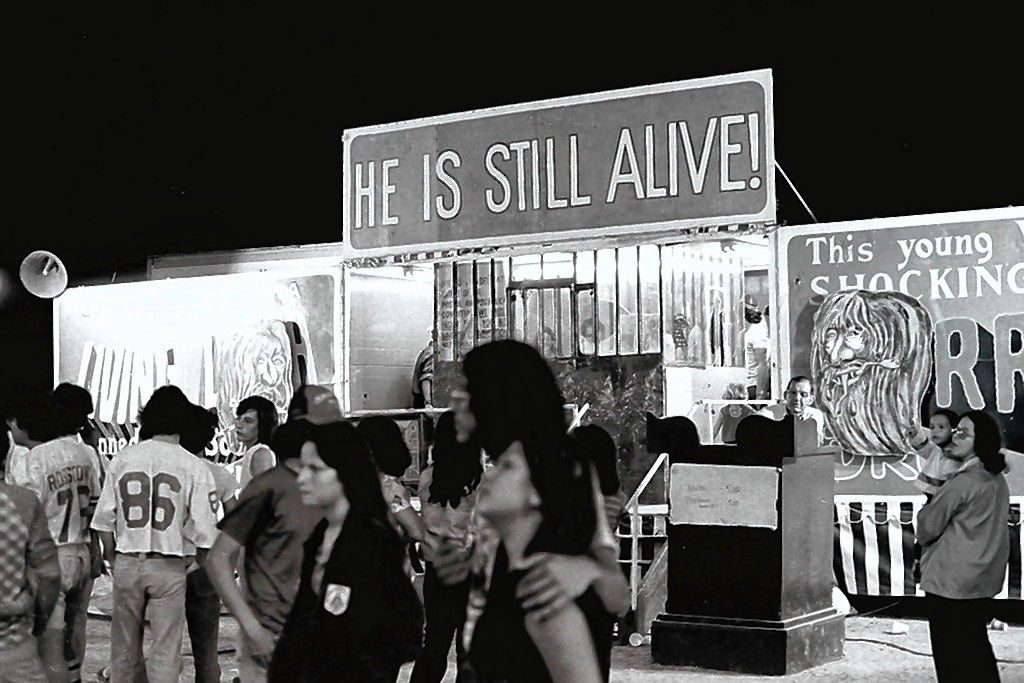

How do we know ourselves? How can we be seen for who we truly are? How do we find redemption in a world that conspires to separate us? Leaf Seligman explores these and other questions in a collection of linked stories from the midway of a carnival traveling through the Jim Crow South in the early part of the 20th century.

From the Midway: Unfolding Stories of Redemption and Belonging traces the journeys of people who travel with a carnival, including the owners, the oddities, and the African American laborers charged with tending them.

Among the characters readers will meet are Lizard Man, who spends his childhood prophesying at the behest of his mother and his adulthood bitterly chasing off what he wants most: human connection; Tiny Laveaux, the “world’s smallest woman” with a larger-than-life personality; Stony, the fossilized boy, and Lisabelle, the dancing girl who tries to offer him joy; 8-foot-tall Leroy Haines who thinks of trees as his brothers; and Cheever whose endless toil threatens to drown him in the Midway mud.

While the strict no-fraternizing policy and the nomadic existence of the carnival create a kind of Noah’s Ark experience for the workers, with the mysterious arrival of a young Jewish singer from Berlin, the Beasleys’ troupe finally gathers on the shores of belonging.

The following is an excerpt from the book.

The Beasleys

After years of selling patent medicines, Earl Beasley stumbled on the perfect curative; he began peddling oddities. Customers suffering from tired backs and rashes, ringworm, itchy feet, even goiters or gnarled knuckles could forget their troubles as they gazed upon the less fortunate. Beasleys’ Traveling Amusements opened its first season in 1910 at the county fair in Tupelo, Mississippi. In the first two years, it traveled to twenty-six counties in six southern states. The lines for the rides and agricultural exhibits remained steady, but the midway always drew the biggest crowd. People munched popcorn and peanuts, licking their salty fingers as they pressed towards the talker advertising a look at nature’s greatest oddities. Outside the tent, the Muscle Man warmed them up with his astounding feats, but the real treasures unfolded inside. Nothing improved the customers’ disposition better than viewing creatures more tortured or ugly than themselves.

Before Earl began hawking distractions, he scoured deep woods and depressed hollows, dispensing tonics, lotions, and other remedies to farmers who couldn’t reach or afford doctors. He might have continued in that business were it not for a Yankee journalist named Samuel Hopkins Adams, who wrote an exposé in 1906 of fraudulent claims and hazardous ingredients in patent medicines. By 1910, some of Earl’s customers grew suspicious, so he hatched a plan.

A meticulous businessman, he had kept records of every customer over the years. He called on Miss Constance Picklesimer whose unusually petite stature he’d been unable to cure, and three years later he offered her a job as the world’s smallest woman. At a stocky three foot-two she wasn’t; but Earl banked on customers who didn’t know otherwise. He gathered six former customers and then hired a line of dancing girls, a talker, and three machinists who could operate and repair rides.

Lizard Man

The first sign that he was different came as a baby when Julian Henry’s mother could not cure his unrelenting rash, but that he didn’t notice until later. Initially, he remembered wondering what was in her cup: the mysterious substance looked like dirt. He kept pointing his two-year-old finger, a lazy way to express his curiosity, but his mother Alice took it as a sign. She had not been particularly religious before her son’s birth. A quiet Presbyterian. But after the first year of trying ointments and remedies, with no relief for her baby’s scaly skin, she began wondering if she had been cursed. The doctor in town diagnosed him. Ichthyosis. Unsightly, not contagious, no known cure. Alice’s sister mentioned the biblical precedent of skin lesions signaling spiritual impurity, though Alice preferred to dwell on Jesus, who healed the lepers, thus suggesting that Julian, because of his suffering, had a special in with the Lord. That set the stage for the miraculous discovery that he had been sent as an emissary to deliver God’s word on earth.

“Sacrifice,” she heard him whisper as she peered at the grounds in her cup. “Give up your worldly pleasure that you might better serve your Lord.” She gazed at Julian, his arm raised, and realized what she had given birth to after all. She had not been punished; no, she had been divinely chosen. Jesus knew she would understand Julian’s powers whereas others, like Julian’s father with his repulsion to the boy’s skin, would completely miss his special gifts. But God knew Alice Henry would see beyond the surface, to look deep within her child’s soul. She passed the test of faith. He sent her sister to fool her, tempt her to turn from her own son, but she alone stood with him, casting no aspersions, never surrendering to doubt.

As she poured the coffee down the drain, her voice crested along the words, Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord. A changed woman, Julian toddled behind her, finally mustering the energy to say “What’s in your cup, Mama?” but in her reverie, Alice did not hear.

When she first sewed wings made of white felt to his romper, Julian felt special. His mother spent an entire day fitting him, positioning the wings, and brushing his hair. When his father arrived home that night, eyeing the outfit, the words fell sharply, the edges scraping Julian even if the meaning landed as a dull thud. “You can dress him any way you please, but he’s still going to have that hideous skin.”

Tiny Laveaux

The house heaved under layers of dust that settled on surfaces above Tiny’s head and beyond her father’s scope of attention, so he hired any one of Ma Bailey’s daughters to cook and clean. No one in town or along the row of farms that checkered the landscape she roamed cared about her size. They had grown accustomed to her, whispering at first, but Tiny developed a mean throw early on, rocks flying like buckshot from her small hand. She earned the distance the would-be taunters kept, and the other children who might have regarded her as the perfect companion – the one they could boss around – quickly learned she bossed them, as if from an invisible throne.

Help came in the shape of a sharply dressed man named Beasley selling patent medicines. Luckily, she answered the door. Her father had gone into town and her mother was resting like she had for the past twelve years. Beasley tried to sell her a tonic to increase vigor and height. Tiny knew better. None of the concoctions her mother had fed her as a child, nor the root woman’s conjures had made a bit of difference. She could smell the snake oil on him. He insisted she try a bottle of his curative free of charge. She thanked him, then watched him leave, the dust from the horses and wagon swirling like glitter before it fell.

She thought he was crazy the second time he knocked on the door three years later, grinning like a jackass when she opened it and he found her same as before. Told her least he could do since the remedy had failed was to hire her for his new endeavor, a traveling circuit of carnival amusements, complete with the South’s largest assortment of natural wonders. He had already contracted the services of three previous customers, and he had more calls to make. He would provide her room, board, and a small wage, but more importantly, he gave her a ticket out.

She kissed her father’s cheek and her mother’s clammy hand and packed one of her father’s wooden crates faster than she could wriggle her way out of groping in Fred’s lap. Better than any tonic was a chance to travel off the mountain in an automobile. On the brink of 1911, she took the stage name of Tiny Laveaux and rode off with a man who promised to make her famous, billing her as the world’s smallest woman, although Ringling Brothers, Barnum and Bailey Circus boasted a much shorter pair of midgets. Little matter to Tiny who never made it to the circus, or to the throngs of farmers who would file past her. Located next to the fat lady’s booth, Tiny appeared little enough.

Cheever

Cheever arched his back, hands clasped behind, stretching as if he could loosen the muscles tight as the packed clay beneath his feet. He twisted his neck to the left, tilting his face upward until he heard a pop. “Ahh,” he said, the tent light catching the blue and purple dust motes settling on his close-cropped hair. He’d been up since six. By the time the gates opened at noon, he’d worked the better part of the day. Everyone at Beasleys’ Traveling Amusements pulled a long shift, but the seven colored workers who pounded stakes, set up the tents, assembled displays, tended the oddities, limed the privies, and climbed the tallest ladders toiled the longest. Ernie and Martha, the common-law married cooks rose before dawn to feed the shifts of workers: first the midway hands who operated rides and game booths, then the sideshow attractions, followed by the colored workers who lived together under one old army issue tent, furnished with cots and a heavy canvas partition for Ernie and Martha. They were the only hired couple in the Beasleys’ employ. Martha’s parents had worked for the Beasleys before the carnival business started, back when Earl Senior and his brother sold patent medicine. If it weren’t for the other colored folks, Cheever wouldn’t have stayed. Glad as he was for steady employment away from cotton, he missed eating among a passel of cousins, uncles, and aunts.

He left Sweet Water, Alabama, at fifteen, to work with the Beasleys, who offered him three meals a day and life free of farming. Cheever’s father and his seven uncles were sharecroppers, and after watching their toil fatten the owner’s children instead of their own, Cheever decided to join the carnival. He and two of his younger cousins had watched the traveling show chug down the railroad tracks, then snuck to the edge of fairgrounds where Earl Beasley spotted him. Four days later, when the show rolled out of town, Cheever rode with them. For months he missed his mother’s cooking and his sisters’ loving slaps on his head as they urged him into his pre-dawn chores. His three sisters were all older, and though his father said he hated to see his oldest son go, he slipped him a buffalo nickel and told him to spend it when he crossed into the promised land.

Stony

Jim Edward Cartwright fell from a horse when he was ten and broke his back. His parents bundled him in the back of the wagon and carried him into town, figuring they’d save time. The ride jostled things further and the doctor at the county hospital politely informed them that Jim Edward would never walk. He wouldn’t even crawl. Paralyzed from the waist down. Being of modest means, they packed him up at the end of his long stay and brought him home, where he either sat in Grandpa Willis’ wingback chair, or propped in bed all day. His mother had chores and his sisters either helped in the fields or went off to school, depending on the season, which left him to leaf through the Sears Roebuck catalogue his mother placed in his lap.

He liked to study one picture of an object – a pair of men’s workboots, a lady’s bonnet, a maul – and invent a story whereby he would find the object and return it to its rightful owner. After a few days studying the wish book, he jumbled the letters on the tool page and pretended he discovered a new country. Nobody walked there and all the people who scooched around on their bellies or rocked on their backs cheered when he rolled in, riding on a carved walnut throne drawn by two black steeds. He sat above the wriggling subjects as they called up to him and pronounced him king. Then he would get two helpings at breakfast with all the blackberry jam and biscuits he could eat. His mother would have to ask permission from the palace guard who knew to admit her only if she brought more biscuits.

His mother, worried he would get fat, rationed his food. Unable to reach the food unassisted, he studied the pages of utensils imagining something to eat. His mother, looking over his shoulder at spatulas and whisks, quickly flipped to pages of flannel shirts. Plaids and checks did not console him. He wanted smoked ham with red-eye gravy and grits with pools of butter melting under his fork, instead of the stingy portions his mother doled out.

Leaf Seligman began writing during her Tennessee childhood where she encountered the midway, revival tents, and the Civil Rights movement. She has taught writing since 1985, and worked as a minister, jail chaplain, youth services caseworker, and a restorative justice practitioner. She is the author of “Opening the Window: Sabbath Meditations” and “A Pocket Book of Prompts.” She lives in Hancock.