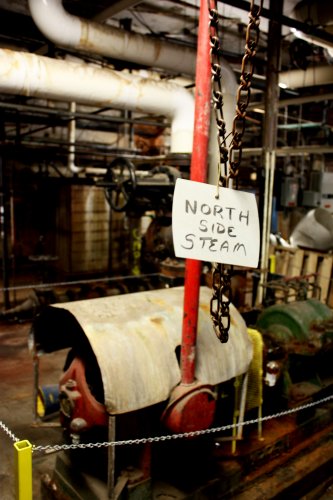

More than 200 buildings in downtown Concord are heated by steam, which floats through an underground network of pipes almost 8 miles long. That unseen labyrinth leads back to Concord Steam on Pleasant Street, a local energy corporation that has been owned by exactly two families in its seven decades of operation.

Cool, huh?

(Well, steam's actually pretty hot, but you catch the drift.)

Meet Concord Steam, a relic in the utility business in that it blends access to a green product with personal interactions and connections, an approach that is becoming dangerously extinct.

“We have customers that swear by us because we're a local company and we're personable,” Vice President Mark Saltsman said of the company that features 17 employees, many of whom have been there for years. “They know they can call us anytime and we're going to show up.”

The plant was built on Storrs Street in 1938 and moved to Pleasant Street in 1980. The underground pipes are filled with steam generated from on-site boilers and carried to the downtown buildings, and the plant simply monitors the pressure in the steam line to make sure a constant supply is available.

If buildings are calling for a large amount of heat and the levels dip, more steam is pumped in. If levels get too high, steam is let out.

Steam is an intriguing energy option, President Peter Bloomfield said, in that it's “already a finished product” when the customer receives it. It's also remarkably green, given that the water is clean and the Concord Steam boilers are fueled entirely by wood chips.

What's more, the wood is local. Much of it comes from a lumber yard the company operates in Pembroke, and the rest comes from a variety of local loggers. During the busiest season, Concord Steam receives 15 trailer loads of chips per day, which are stored in a pair of silos, each with a capacity of 650 tons.

So how fast does Concord Steam go through the chips? Salstsman said if the silos are filled on a Friday afternoon, they will be nearly empty by Monday morning. The company goes through 50,000 tons of wood per year.

“Our intent is to provide quality with low emissions,” Bloomfield said. “Wood is naturally clean, and we burn it hot and hard so it stays clean.”

The facility operates one, two or three generators, depending on the need, with the furnace reaching a temperature as high as 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit. Each wood-burning boiler runs on oil for a half-hour once every 12 hours in order to have the grates cleaned out, but otherwise operates without assistance.

Steam's many green benefits keep it a viable option in the energy market, though competition has made things more difficult. Because of the cost of running steam pipes to inpidual residences, only one residential home in the city can still boast steam heat. And as gas prices have continued to drop, steam has become a less affordable option to some.

But Concord Steam has seen fluctuations like this before. Steam came into vogue in the 1930s as an alternative to coal, which was producing thick black soot and other street-level pollution, and has battled a roller-coaster ever since.

In 1977, because of the oil embargo, oil was projected to reach as high as $150 barrel, Saltsman said. It never got that high, but reached a peak of $50 before plummeting back to $14 in the 1990s. What's complicated things recently is that gas has become cheaper as oil becomes more expensive, marking “the first time in 30 years I've ever seen oil and gas separate,” Saltsman said.

“The cheaper product always wins the day,” Saltsman said. “Our biggest challenge is convincing the customer to ride out the storm that makes us not competitive for that snapshot in time.”

Steam's biggest advantage in that battle is its stability. Though certain costs fluctuate naturally – ironically the cost of oil has an impact because of the fuel required to deliver the wood chips – steam carries an overall steady cost.

“We're not subjected to the volatility of the petroleum markets. There's much more stability,” Saltsman said. “Prices can rise, but there aren't real high peaks and low valleys. Budget stability is really important, and that's something we can offer.”

It's not the only thing, though. In an effort to expand services, Concord Steam has been able to heat a handful of downtown sidewalks with residual steam that would otherwise have been lost in the heating process.

As steam is converted back into water, Bloomfield said, you get condensate, which is as hot as 200-plus degrees. The sidewalk system recovers that heat before it goes down the drain and pumps it into tubes with an anti-freeze mixture. As the building requires more heat, the sidewalk gets warmer, allowing snow to often melt on contact.

The Capitol Center for the Arts, the south side of Theater Street and the new Smile Building are just a few spots taking advantage of the system.

Concord Steam has been hoping to relocate for several years, and has a project in the works to create a new plant on South Main Street, a relocation Bloomfield said he hopes is complete by the end of 2013.

Either way, though, Concord Steam expects to remain viable in the current energy battle.

“Any struggles we've had recently have been because we're competing against natural gas, that's our fiercest competitor,” Saltsman said. “But natural gas at some point will go back up, and we'll be a better deal. There's always a back and forth.”