For Michael Leuchtenberger, perception and reality collided somewhere in the Burundi countryside.

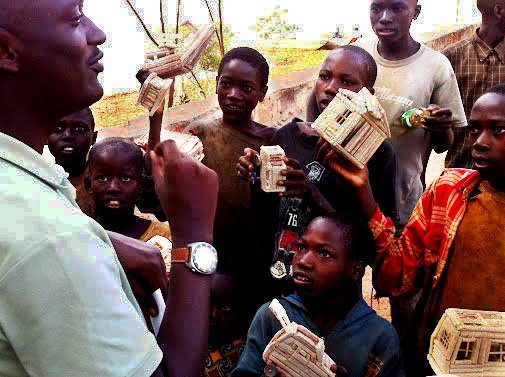

Leuchtenberger, minister of the Unitarian Universalist Church in Concord, was briefly mesmerized while touring the nation during an August trip to help strengthen a burgeoning congregation. Tiny mud huts with thatched roofs that housed entire families, as well as goats and other livestock. Children running through the streets in tattered T-shirts with no shoes on their feet, or piling onto the backs of bicycles in packs of three or four. Women hulking heavy loads through the village on the tops of their heads.

It was quite a scene. Until Leuchtenberger realized it wasn't a scene at all.

“At first it almost had sort of a postcard feel to it, like, oh, this is kind of cute,” Leuchtenberger said. “And then to have it sink it and think, this is people's lives, this is not cute. How are they going to live off a tiny parcel of land, off the banana trees they have here? How are their kids going to possibly have a chance to develop into a life that doesn't make them dependent completely on the whims of nature?”

It's a moving question. And if things go according to plan, Leuchtenberger and his congregation will be involved in helping to find an answer.

Leuchtenberger's visit came about as part of a project organized by a trio of Unitarian ministers from the United States who were joining forces to help develop leadership in a fledgling Unitarian congregation in Africa, where the Catholic faith is the dominant religion.

Over the last five years, under the leadership of a former Dominican minister, a group of about 70 people in Burundi has come together in pursuit of a “more liberal faith,” Leuchtenberger said, forming their own congregation. A minister in Kalamazoo, Mich., has been involved with that congregation and wanted to explore something outside of the usual one-to-one relationship that often exists between churches, instead hoping to join forces to open more doors in African nations.

“There are emerging groups of people who seem interested in Unitarian-type religious organizations, and the reason for us going over there was to meet with some of the leaders that are beginning to emerge there and come up with a strategic plan for how we can be supportive of each other in this process of ultimately growing congregations,” Leuchtenberger said. “And the initial step is how can we develop leadership there.”

Some leadership has certainly already emerged in the Rev. Ndgijimana Fulgence, a Burundi native and the man who helped form the new congregation. But to fulfill the mission of expanding the faith, more was necessary.

To that end, a pair of young men have been chosen essentially to be ministers-in-training, an experience that will likely include a trip to the United States to view and experience some Unitarian services. An October appearance by a leader from Bujumbura, the capital of Burundi, is planned in Michigan.

That mutual partnership is one of the major tenets of the project, as Leuchtenberger said he hopes to be able to learn as much from the African ministers as they can from him, and to let them have a great deal of autonomy as they develop their faith.

“It's wonderful to see the potential of what could happen with our involvement in this partnership, and to see the potential both for our contribution and in reverse in them offering things to us,” Leuchtenberger said. “Us as visitors and the folks locally in Burundi have been very aware that we don't want to fall into the trap of 'here are the rich people coming to donate.' We really wanted to make this a mutual give-and-take partnership, and that's the struggle I think, trying to figure out right now exactly how that can look. But we're very concerned about not wanting this to be us going over there telling them what to do. It's really about them figuring out as much as possible what they need and what they want to see happen.”

The initial visit led to the groundwork for the project, which will include a leadership retreat sometime in the next six months, featuring leaders from four or five different countries in Africa, as well as one United States representative, though much of the work will be led by the native leaders.

Those who made the August trip were hesitant to set too much in stone beyond that initial retreat, but have put in motion a two-year plan that will be revisited in order to determine the best course to continue the progress in strengthening and developing congregations.

Though the trip was Leuchtenberger's first to Africa, he had developed some Burundian connections on his home soil. The Concord church began in 2008 welcoming refugee families by forming a “circle” of support around them, essentially giving the families a network of friends to help with things like navigating the health care and school systems, learning English, finding bicycles or cars to purchase, or opening and operating a bank account. The first such family was from Burundi.

Concord boasts a fairly strong Burundian community, and for those who live here – even those who aren't part of the Unitarian church – the connection between the nations is an important one.

“It's very interesting, because we need something good in my country,” Jackie Manirambona, who has lived in Concord with her husband and children for six years, said. “So I feel happy for that.”

Manirambona left Burundi because of the civil war that devastated the region, spending four years as a refugee before even arriving in the United States. Though she was raised Catholic, she has since become a member of the Seventh Day Adventist church, and she attends one here in Concord.

Regardless of which church you attend, she said, faith is extremely important in Africa, and was particularly critical when times were hardest.

“Church helped a lot during war,” Manirambona said. “It helped people pray, that the war will go over so we will be able to survive.”

Leuchtenberger learned first hand how important it truly can be. One of the ministers in training lost his brother to the civil war, and spent a great deal of time scheming a bloody response.

“He spoke of how his brother had been killed, and his immediate impulse was to want to take revenge. That was all he could think of,” Leuchtenberger said. “The problem was his brother had been killed by a whole group of people. How do you take revenge on a whole group of people? It took him a long time to get to that place of 'revenge is not the answer here. I need to find some way of reconciling terrible deeds, but for me to find peace, revenge is not where I need to go.' “

Though war has subsided, conditions remain difficult. Leuchtenberger toured a school for more than 1,800 children in grades 1-6 that has but seven classrooms. There is no running water and no electricity, and though the students meet in two shifts, there are still about 80 children to a class.

There aren't enough books written in English for all the schools in Africa to own, so instructors teach out of suitcases, which are shipped to the next school once lessons are complete in order to maximize resources.

“Many of the kids have a T-shirt or two that they own, and to think, how are they expected to learn what they need to learn?” Leuchtenberger said. “And for the teachers, they just don't have the resources to do the job the way I know they would want to do it. I have kids myself, and to think, wow, that would be a very different learning experience for them.”

Despite the surroundings, Leuchtenberger said he felt a warm welcome from the start. Though he was often the only white person in the villages he visited and was referred to by the generic Swahili term “mzungu” – which he said loosely means “a person who just sort of loafs around and doesn't do anything other than ordering people around” – the citizens were generous and genuinely interested in his life.

“I was certainly a curiosity, but it was a very friendly curiosity. It wasn't a hostile look I've experienced in other countries,” Leuchtenberger said. “The welcome that I felt was quite amazing, the warmth with which people were interested in showing me around and showing me their country.”

He hopes to see more of it, though no future trips have been officially planned. But the partnership will certainly continue, and along with the leadership retreat the groups in America and Africa are also planning something of a shared worship, where congregations in both countries perform the same service, with the same music, on the same day, perhaps with live messages shared via Skype, if possible.

And the seeds have certainly been planted for similar cooperation, which Leuchtenberger believes will benefit everyone involved equally.

“We're toward the end of rethinking our mission and vision (at the church in Concord), and a core piece of our identity seems to be evolving toward welcoming people from different walks of life, different cultures, into our community, and that is both the community here at church and also the larger United States community and Concord community,” Leuchtenberger said. “Sort of being bridge builders across cultures, and I think this becomes just one more way to build bridges. It's the social justice side of being relevant to the lives of the local population in its many different ways, and through exchange, learn from each other and help each other to become more fully human.”