With 49 years in the business of selling music, Michael Cohen has seen about everything. Lately, he’s seeing it all over again.

“It’s gone back to the beginning!” said Cohen, the owner of downtown mainstay Pitchfork Records & Stereo, sounding both amused and a little incredulous.

Cohen was a student at Henniker’s New England College in 1972 when he and some friends started selling vinyl records – then called LPs or long-playing records to differentiate from single-song 45’s. He says he wasn’t particularly a music aficionado; it just seemed like a fun thing to do. Then the friends wanted to sell out so he bought the business for the princely $400 in 1973 and hasn’t looked back. (The name pitchfork is a reference to Henniker’s agricultural history, by the way; the online music venue of that name came along decades later.)

Cohen quickly brought the store to Concord. Over the years, as LP records gave way to 8-tracks and cassettes and CDs, he moved up and down Main Street before settling 13 years ago into his current high-profile spot at the corner of Pleasant and North Main streets, formerly home to Foodee’s.

“It’s the best location in Concord,” he said. “We see everything. We see more than we want to see, sometimes.”

Pitchfork Records is a monument to the surprising resurgence of vinyl records, which have not only come back from the dead but in 2021 actually out-sold CDs in this country. “If you had asked 5 years ago if it would last I would have told you no, but it keeps on getting bigger and bigger and bigger,” said Cohen.

Much of Pitchfork’s business revolves around LPs. That includes hundreds of used ones that Cohen buys from people who (like this reporter) are unloading their no-longer-played collection for a lot more than once seemed possible.

“That’s probably 20%, 25% of our business. The customer comes in, they’re downsizing, and it’s a win-win-win. They win by selling something they don’t need; we win because it’s business for us; and the buyer wins when they get a record they want,” Cohen said. “It’s the most profitable part of the business.”

The only non-winners are the older folks who lament that they gave away or dumped their old records years before.

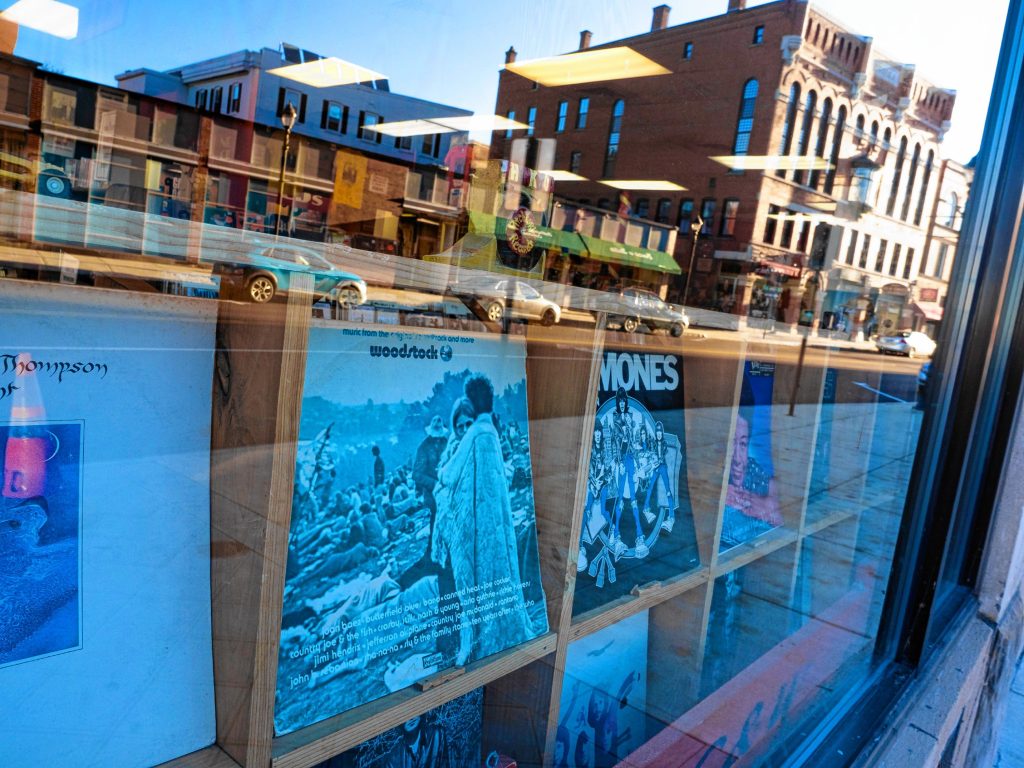

Pitchfork sells plenty of brand-new records, as well, both reissues of classic albums and newly pressed releases from current artists. The store also sells a number of different turntables so you can spin your analog tunes. And although new and used CDs remain a big chunk of the business, as well as posters and other music paraphernalia, it’s vinyl records that fill the windows and give Pitchfork its retro/modern aura.

“Customers are young, they’re old, people that have been shopping here the whole time he’s been open, a lot of teens from St. Paul’s come in and buy posters and vinyl. There’s a huge range of people,” said Dre Svensson, a 2012 Concord High School graduate who has worked at Pitchfork three years.

The appeal of vinyl, she says, is multifaceted. “It’s the whole experience of looking through them and finding stuff that you have no idea what it is and buying it because you’re curious, and there’s all the new vinyl, remastered and re-pressed, and all the new artists you can get. It’s everything,” she said.

Perhaps surprisingly, Cohen said the advent of digital music and online streaming, which has devastated the finances of record companies and recording artists, hasn’t hurt him. Maybe it even helps.

“People hear something, then they come in and buy a physical product. They don’t want it just on the phone; people want to own something,” he said.

Pitchfork’s building is owned by Endicott Furniture, which Cohen calls “a great landlord,” and assuming music-buying trends don’t take some weird unprofitable turn – presumably not even the most old-school-loving fan is going to start demanding 78’s or Edison wax cylinders – Pitchfork should stick around for a while.

“We’re an institution now,” Cohen joked.