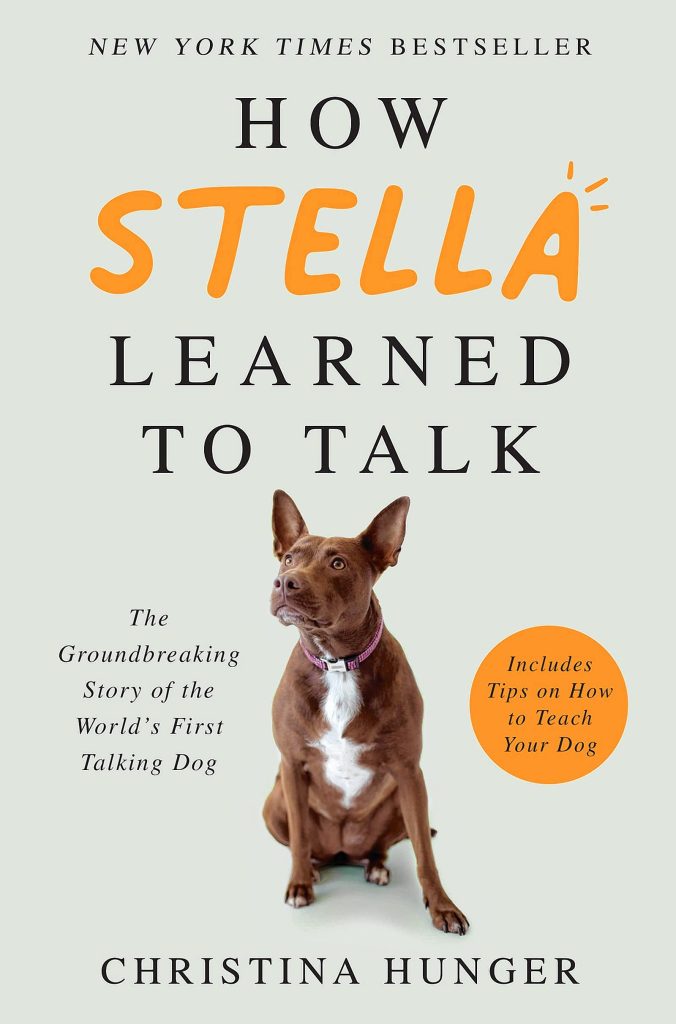

How Stella Learned to Talk: The Groundbreaking Story of the World’s First Talking Dog

By Christina Hunger

(260 pages, memoir, 2021)

How Stella Learned to Talk is one of my favorite books published in 2021. This light-but-fascinating read willappeal to animal lovers, parents of young children, or anyone interested in language acquisition and verbal communication. Part memoir, part popular science, this is the story of speech-language pathologist Christina Hunger, who applied the principles of (human) speech therapy to her puppy, Stella, to help Stella learn to communicate with people. The results of their informal experiment blew me away. After reading this book, be ready to reevaluate how you think about animal cognition and emotion.

Hunger’s interest in animal communication is no coincidence. In fact, her profession is to help human children learn self-expression through Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) devices: think of touch-screen tablets with pre-entered words and phrases, which allow Hunger’s clients to convey thoughts and feelings that they are unable to speak aloud. After acquiring puppy Stella, Hunger decided to institute a similar setup at home. Lots of dogs are trained to ring a bell hanging from a doorknob to request a trip outside, Hunger noted — but what if Stella needed something other than a trip to the backyard? It was this question that led Hunger to design a bespoke AAC device for Stella.

With rigorous training, Stella learned over time how to express her thoughts and feelings by pushing buttons with her paws — first one word at a time, and then (I promise I am not making this up) in short phrases and sentences. This is far beyond “sit,” “stay,” and “bone.” This good girl can actually let her humans know that she wants to go to the “park” to “play” with “Jake” because it makes her “happy.” There is ample video evidence available on Hunger’s Instagram, YouTube, and personal website (search for “Hunger for Words”). I’ll also add, for my fellow skeptics, that Hunger makes it clear, in the way she sets up and writes about this experiment, that Stella does comprehend what she is saying, versus simply mashing buttons with her paws. One thing I really love about Hunger’s writing style is that she delves deeply into the “how” and “why” of each decision regarding Stella’s AAC device. She truly seems interested in helping her readers to grasp the concepts at work: why, for instance, certain touch-pad configurations are more helpful to language learners than others. This book is rich with “take-aways” to help readers teach their own pets using AAC.

At its heart, this is a story not just of one woman and the seemingly miraculous communicative achievements of her canine companion, but of the unplumbed depths of animal cognition. There is so much we don’t know about how other species understand the world! Hunger’s work breaks down human-centric ideals, forcing us to confront an animal kingdom replete with autonomous, thinking, feeling individuals. While humans have assumed, all this time, that animals lack the capacity for complex expression, perhaps we simply lack the tools to listen effectively. The implications of this, of course, are that our animal neighbors are deserving of respect and dignity, and that there is far less difference between “us” and “them” than was previously believed. It’s that combination of heart-plus-brain that makes this book a “win” on so many levels.

Faithe Miller Lakowicz