We could argue all day about whether it was Plato or Socrates who first coined the phrase “Go big or go home.” What’s not up for debate is that photographer Thomas Wright’s project at the Concord City Auditorium has certainly gone big. And he hasn’t really gone home yet.

What began as a modest undertaking to shoot some panoramas in Concord’s fabled theater has turned into a three-year labor of love for Wright, who is still sifting through mountains of images from numerous visits to the city.

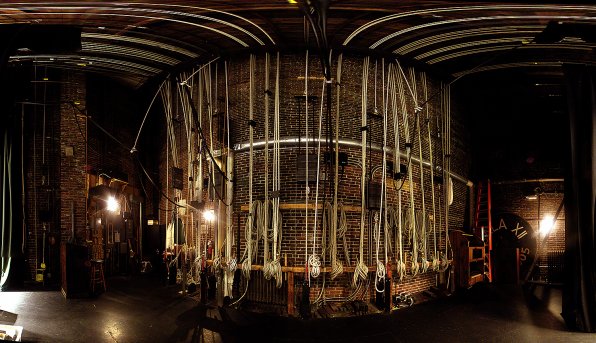

“I figured it would be six months and a few hundred shots, not three years and 3,000 shots,” Wright, who lives in Goffstown, said. “One thing that has happened as I’ve been going back through them is I’m gleaning more out of this collection. I’ve done about a dozen photo shoots (there), and it’s whatever jumps in front of the lens. Clearly, the pin rail system is a major focus, but there are so many other things, from light fixtures to an inpidual chair with numbers on it and details like that. The piano at center stage, but with the lights lowered, creates a very interesting mood. Every time I go in, I see something new. And sometimes I don’t even see these things until I go back through and I’m looking at the shots afterwards. There’s always images within the image and things that all of a sudden appear that you didn’t even see.”

The project began innocently enough when Wright attended a presentation in the Audi lobby and got a peek at the full auditorium. He immediately thought of shooting some internal panoramas, and before long was discussing a project with Carol Bagan of the Audi. There had been talk of replacing the old pin rail system, Wright said, and the Audi wanted “to get a photographic historical snapshot” as things stood first.

Of course, a potential agreement hinged upon the elephant in the room in most modern deals: an arm wrestling match.

Actually, it was money. And it turns out Wright didn’t want any. Which worked out well, because the Audi didn’t have stacks of extra bills to start handing out.

“That happened in the first 15 minutes of talking with Carol,” Wright said of the decision to make the project a gift to the Audi. “Once I saw the auditorium, I wanted to shoot it. And they really wanted someone to capture the pin rail and other aspects of the auditorium. We said, ‘This has the makings of being a win-win situation.’ After about 15 minutes we realized neither of us was really interested in money.”

Wright simply wanted the images, and the agreement signed allowed him to retain all copyrights, giving him the right to sell them down the road. The Audi, meanwhile, was to receive large-scale prints of several of Wright’s photos to form a gallery in the lobby.

“To me, the interesting part of his work is the way he sees everyday pieces of the theater, such as the rope rigging or the light fixtures, as works of art,” Bagan said. “Another sidelight – Tom’s work is a gift, and the Friends of the Audi would never have been able to afford this project. That in itself is pretty amazing.”

“We said, this is not about money, this is about art and this is about architecture and history,” Wright said.

It certainly became about much more than just the pin rail system. Wright wound up with plenty of those images, for sure, and he also snagged his sought-after panoramas, but what started as a quest for a few snapshots quickly took on a life of its own. In the end, Wright wound up memorializing almost every tiny detail in the auditorium, from the seats to the stained glass in the lobby to ceiling fixtures, and returned to capture the theater in action, spending an afternoon shooting a performance by the Granite State Symphony Orchestra.

“The whole project kind of morphed – it was supposed to be an historical photographic snapshot, but it became much more. There’s a story here to be told. About the Audi, how it’s used, and the groups that use it. What’s the story of the pin rail system itself? And the stained glass, which used to be in a church down the street.”

The images given to the Audi are hanging in the lobby, highlighted by the pair of panoramas, one from the balcony sweeping across the stage and the other from the stage looking out into the auditorium. The panoramas are 24-by-36, with the other handful of detail shots in smaller formats.

Snapping the pictures may have been the easiest part of the process for Wright. Photo editing has absorbed the bulk of his time, whether its removing the ceiling behind an ornate light fixture and replacing it with a black background or piecing together the panoramas, which are each constructed of more than 100 inpidual shots.

Each one features three layers, with each layer composed of 36 images in four rows of nine. Each layer features a different exposure – one for midtones (or normal exposure), one that is underexposed and one that is overexposed. The underexposed shots allow the camera to better see into the highlights, Wright said, while the overexposed images allow it to see into the shadows.

The puzzle becomes putting the layers together to create the final product.

“Every single point source of light – every sconce on the wall, every chandelier – I went to the underexposed image that included that piece and layered it over the normal image and blended it,” Wright said, describing the process that allowed the lights to most effectively shine through in the final product. “What I’m doing by using these techniques is producing an image that is closer to what the human eye sees. Through techniques like this I’m enabling an image to be actually more like what we see as human beings.”

If Wright has anything to say about it, he’s not done seeing things at the Audi, either. Though he’s provided the initial prints and will provide the Audi with the raw images for their archives, he’d like to continue the project indefinitely.

After all, why go home now?

“This project may not end for a long time,” Wright admitted. “There may be other opportunities to come back and do additional shoots and some additional work. We basically have a working relationship now.”