Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Barbara Walsh will be in Concord on March 15 to discuss her latest book, August Gale, with an appearance at Gibson's Bookstore at 7 p.m. The book weaves two tales together – a deadly Newfoundland hurricane that took the lives of hundreds of fishermen and the tale of her father's childhood pain after his father – Walsh's grandfather – abandoned the family.

Walsh journeyed as far as Newfoundland, where her grandfather, Ambrose, was born, and unearthed a trove of family stories along the way. Ambrose lost family members and many friends in the deadly hurricane, discovering the news only when he stooped to pick up a newspaper that stubbornly blew around his ankles while he sat on a Brooklyn pier.

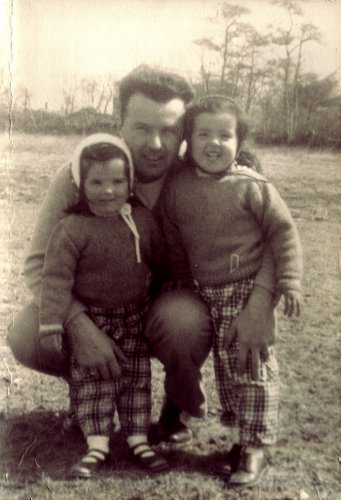

Ambrose later left his wife and children – including Walsh's father, Ronald – twice in a three-year span, eventually starting a new family in California but leaving painful scars in his wake. Following the trail from Newfoundland to parts of New York and the West Coast, Walsh and her father are able to piece together a picture of the man Ronald will never forgive but always remember.

Walsh grew up in New Hampshire and graduated from UNH before embarking on a journalism career that ultimately netted her the aforementioned Pulitzer. She has also published a children's book, Sammy in the Sky, a story about the death of the family dog.

We caught up with her for a Q&A. Read all about it.

You've obviously written about many perse and sensitive topics during your career as a journalist, but how different was it to write about yourself and your own family's history?

This book was definitely the hardest thing I've ever done in my career because it involved family. My dad, writing about his childhood was really tough because I'm writing about a very painful time in his life, so I struggled in how do I tell that story? I initially tried to tell it from my dad's viewpoint, but I realized that I couldn't, so I decided to tell it from the daughter's viewpoint, sort of a daughter listening to her father telling these stories and reacting to them. I would cry when I wrote some of the chapters, or tear up when I read them at book talks, because it's still very emotional. That piece was really challenging,

And then, with memoirs, you have to write from truth, so I couldn't gloss things over or try to make it like it wasn't so hard. My dad, I worried for nine years what he was going to think about (me telling his father's story). He said, “It's okay, I trust you.” It's really two stories – the real storm and the family storm – and I had to weave those together because the book alternates in time, between the history and back to the present, so there are a lot of parallel themes.

Both of your books are written about emotional family situations. What inspired you to start writing about your own family?

After I saw the movie The Perfect Storm, something really resonated with me, because I love the sea and water. My ancestors were all fishermen, and I thought, “I can do that.” I sat in the theater and it really resonated with me. One night at my home in Maine in February 2002, I said to my dad, “I want to write books.” He said “What kind?” I said, “Sort like The Perfect Storm,” and he said, “You have a story like that in your family.” So he started telling me about the August Gale that killed several of our ancestors, and he had never told anyone the story since his mother told him 40 years earlier.

The other piece was my father said, “Maybe we can get in touch with family.” My grandfather, for 65 years, really refused to talk about any of it. But all of a sudden this story opened up about our ancestors in the storm, and in learning about Ambrose we went to Brooklyn and Staten Island and other places. It's ironic that the storm that ripped my family apart pulled us all together. We now know my Newfoundland family and Ambrose's family in California. It's an incredible story.

How different was it to write August Gale as an adult biography and memoir, as compared to Sammy in the Sky, which is a children's book?

A children's book is so much easier in the sense that it's a lot shorter, and even though it's about the death of our family dog, it's something I was able to write more quickly after our family dog, Sam, died. My two daughters were almost 6 and 3, and it was their first experience with death, so they kept asking me questions. Emma would say, “Why can't he come back?” Nora would stare up at the sky and point and say, “Sammy, you come down here,” like he was just being bad, or she'd say, “Maybe if Daddy gets a really big ladder we can get him down.” I kept writing down what they said, and pretty soon I thought, I have a book. It was difficult to sell because agents told me it was too real, too sad. I said, “That's the point.” There's nothing else out there that deals realistically with this stuff.

Is there any particular moment from the journey to Newfoundland that stands out as especially moving?

I was interviewing one man, named Michael Farrell, who had lost his father in the gale. Dad and I were both in his kitchen, and it was difficult to understand him with his accent. It was almost like we were playing charades almost. But I learned he was a year old at time of storm, so he never had any memory of his dad. All he knew was his dad was lost on a schooner. He just kept saying, “My poor daddy was lost.” When we left his house and we were walking up the sidewalk to the car, I thought about my father losing his dad. Ambrose was my father's hero, and he abandoned my dad at age 11, and after reconciling in San Francisco he abandoned him again at 13. I was looking at these fishermen's children, kids who lost their dads to the sea, and my father lost his dad to bad choices. There were a lot of parallels to these kids who missed their fathers and grieved for their fathers. There was a lot of a similar sense of loss and grief.

Was your father able to reconcile any feelings for his father after having undertaken the journey?

One of best things is he didn't know any of his Newfoundland relatives (previously), and they are just incredible. They are so hospitable and can't do enough for you. It just opened up a door for him of relatives he had never met. And inviting Ambrose's daughters from California, they had always felt guilty for what my father went through. My father won't ever forgive Ambrose, but it's been very cathartic because he never talked about any of this for 65 years and now it's out there, which was an incredible gift to me, that he trusted me to tell this story. In some ways it's good because this was all kept inside and now he's talking about it – with me at book talks, or he's always talking to people about the book. It certainly brought us closer, because we traveled together and met family we had never met. The Walsh clan has expanded, I guess, and it really has been a lot of fun.

You've been to Ireland and spent time in Newfoundland, so you must have some deep Irish roots. What does it mean to you to speak at a St. Patrick's Day event?

That's part of the reason we are kind of promoting it that way. Pretty much most of the characters and people in the book are all Irish, and many of those Irish superstitions came over with all these people, from Ireland to Newfoundland. They were all very superstitious.

The wives of these fishermen wouldn't turn cake pans over to get cake or bread out while the men were out at seas because they were afraid the schooners would flip over. And when men died at sea, a lot of the wives would see their husbands walking down the hall in their homes in their oil skins.

A lot of family members talked about seeing the fishermen return to Marystown on the night of the gale. It was just wonderful, because a lot of times it felt like I was in Ireland.

Related content: